Recently, I have been spending a fair bit of time on Reddit’s productivity subreddit board (r/productivity). A common theme that I have come across on the board is a blatant misunderstanding of productivity. All too often there are individuals asking “How can I be more productive” or “How can I do more in x amount of time” without understanding just how productivity works. To be fair, this is not something that I have only come across on reddit, but also on other websites, forums and even in published works, videos, etc. I touch on this issue as well in my upcoming book, The Tempo Productivity System, and elaborate on this further with an introduction on pseudo-productivity. For this week’s productivity post, I want to actually focus in on and help you understand just what productivity is.

So let’s start with the basic question: What is productivity?

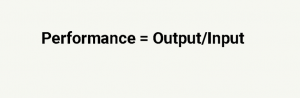

The textbook definition of productivity is as follows: productivity is the yield or ratio between the values that are input in a system compared to the output. More simply, it is what you get when you compare what you put in versus what you get out. In essence, that is the basis of production.

Whatever you put in determines what you get out. At least in theory. Human productivity in action is much more sophisticated than that and often creates a bit of a paradox. If we simply throw a bunch of variables into a productivity system, and expect some great outcome, we will be disappointed. This is because human productivity is not based on an absolute value solely determined by input/output, but more so how relative it is to input variables and constraints.

To understand this, let’s take a look at productivity in action using the following example:

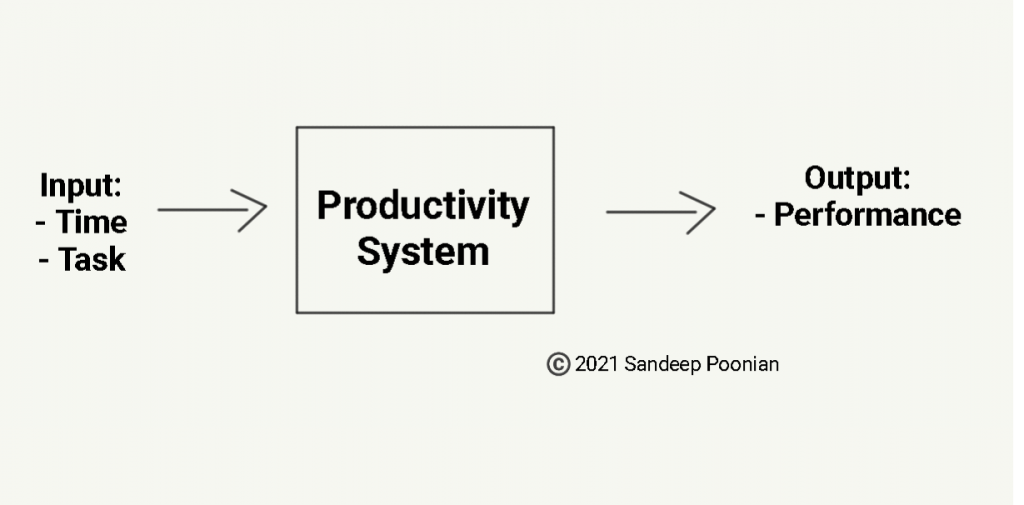

Two individuals are tasked with vacuuming an average sized empty bedroom. They must complete this task in 5 minutes. Each individual is given the same vacuum and we can assume all other conditions are factors are the same. Based on this, we can draw up the following diagram:

As you can see, the values that we input are time and the task. We get each of our individuals to perform the task while recording the time it takes to complete the task. Individual 1 completes the task in 1 minute and 30 seconds. When we evaluate the time that was given vs the time it took to complete the task, we see that individual 1 took close to a third (30%) of the time required to complete the task. Now, let’s take a look at individual 2. Individual 2 completed the same task, however they completed it after 4 minutes. It took them 80% of the time that was given to them to complete the task. When we compare the outcomes between individual 1 and 2, it’s quite easy to determine that individual 1 was more productive than individual 2, having completed the same task much more quickly than them. In this scenario we have a way to measure the relative value of productivity based on our understanding of input/output in production so far.

The next part however is where it becomes a tad bit difficult. When we go back and take a look at individual 2’s performance, we notice that during vacuuming, there was a problem with the vacuum wheels jamming. Because of this, it took individual 2 longer to complete the task. This error is another variable that we must place in the input category of production. So now, when we determine individual 2’s productivity, we assess it based on all conditions that affected performance. If we were to run the trial again, after fixing the vacuum, we should expect to see individual 1’s relative productivity increase. And sure enough it does. After running consecutive trials, with other subjects under the same ideal conditions, we may be able to obtain an average range for how long it takes to vacuum an empty, average sized bedroom. From there we can extrapolate the data and assign the baseline for production required to complete the task, and then use that baseline for the measurement of our absolute productivity for this simple and specific task.

Measure of absolute productivity does get more complicated when tasks become much more sophisticated and are impacted by numerous input variables. I like to consider both internal/external variables that can affect input. Emotional states, physiological needs, motivation, and time to name a few, are all internal/external values that can have an impact on performance, thus affecting absolute productivity. This becomes a problem with complexity making it harder to determine a baseline measurement for absolute productivity overall. At the end of the day, we can only determine the relative productivity or a complex task by measuring performance based on the variables that are entered into a system.

So when people ask, “how can I be more productive?”, “is my productivity high”, or “how can I improve my productivity?” we really need to counter it with another question: what is it relative to? Strategies and tips that are provided to “increase productivity” must only be used to manage and reduce the strain that variables have on a system. It is why it is silly to suggest that you can be productive if you do “x” or that you can become more productive overall with the snap of a finger. We cannot completely measure productivity. But we can assess performance based on our understanding of the input/output system and efficiency, which I will talk about in more detail in the near future. For now, that’s all.

Until next time.

~ Sandeep